Differences in Music within Buddhist Sects

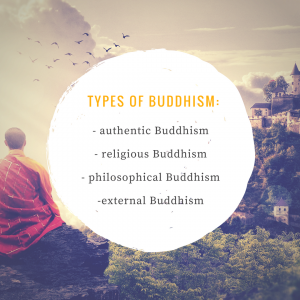

Master Chin Kung, a teacher and student of Buddhist thought for more than fifty years, describes to us the four common types of Buddhism in our world today (AMTB.org):

- authentic Buddhism

- religious Buddhism

- philosophical Buddhism

- external Buddhism

Religion, among many things, has evolved over the generations to include many different lifestyles and intents behind the daily or weekly practice. In the same way that every person is unique and different, every religion can be viewed as unique and different as well – given that similarities may be found (such as the overarching description “Christianity” or “Buddhism”).

Regardless of the large differences between religions found around the world, there are also differences between religions in the same region. So, we cannot forget there are differences (sometimes subtle) between each sect. In most cases religion, among other things, relies heavily on music or sound-making and Buddhism is no exception. Just as differences are found in religion, differences can also be found in their music

As Ge Zhuang states in his article “A Survey Of Modern Buddhist Culture In Shanghai” in the journal Chinese Studies, “different religions feature their own integrated doctrines, canons, rituals, and organizational forms” (79). Between the different kinds of Buddhism, music often varied to suit and rise to meet individual cultural and historical influences.

So – the goal of this article is to evaluate the differences in the use of music in Buddhism between different religious sects, namely:

- Theravada Buddhism

- Mahayana Buddhism

- Tibetan Buddhism

The strategy in which this information will be presented is based on a brief analysis of the major differences between these Buddhist sects, analysing the history behind them, and the kinds of Buddhist music. With this context, we can then attempt to describe modern observations of Buddhist music today.

________________________________________________________________

Quick History of Buddhism

Differences in the Buddhist sects are important to understand before diving too far into the history between them so to quickly determine these differences, we will look briefly at a larger scale of Buddhism in its entirety. Buddhist sects have similarities in their main ideas: all have an emphasis on the search for a correct understanding of human nature and ultimate reality (Bhaskar 78). The main teacher of Buddhism was Buddha, also known as Siddhartha, who was the first to find and experience enlightenment (a state of perfect understanding, happiness, and peace) occurring around 2,500 years ago (Bhaskar 79). All Buddhism has a similar main objective to help one another reach enlightenment, just like Buddha.

Three Types of Buddhism

There are three main types of Buddhism: Vajrayana (Tibetan), Theravada, and Mahayana (Bhaskar 81).

- Vajrayana (“Diamond way” or “Thunderbolt Vehicle”) developed in the fifth century C.E. in India and spread to Tibet where the office of the Dalai Lama was centered (Bhaskar 154). The Vajrayana’s purpose in life is to turn poisons of craving, aggression, and ignorance into wisdom to better separate the mundane world from enlightenment through the help of the current Lama, already in an understanding of enlightenment” (ReligiousFacts.com).

- The oldest surviving branch of Buddhism is the Theravada (“Teaching of the Elders” or “Southern Buddhism”), beginning in the 4th century B.C. E. involving monastic practice (Bhaskar 113). The Theravada purpose in life is to become an arhat, a perfect saint who has achieved nirvana and will not be reborn again. This being quite different from Mahayana.

- Mahayana (“Greater Vehicle” or “Greater Ox-cart”) emerged in the first century C.E. as a more liberal and accessible interpretation of Buddhism because the “path” to enlightenment was available and achievable to all walks of life, not just monks and ascetics (ReligiousFacts.com). The purpose of life for a Mahayana Buddhist, which differs from that of Theravada, is to become a boddhisatvas, a saint who became enlightened by unselfishly delaying nirvana to help others attain it as well (ReligiousFacts.com)

As V.S. Bhaskar stated in the book Faith and Philosophy of Buddhism, “many [Buddhist] sects disagree in many fundamental ways and comparing them to one another is like comparing two separate religions” (55). Between Theravada Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism, according to Lyu Shr Heng in an article from Religion: East and West published in 2012, their essential mission is to “cease all unwholesome conduct, do only what is good, and purify your mind” (46).

Although Tibetan Buddhism originates from Mahayana beliefs, its geographical separation from that of China and other Buddhist areas coerces a researcher into studying them separately – not only that but Tibetan Buddhism is led primarily by the world-renowned Dalai Lama, who “has an enormous following” (Bhaskar 168) in the Tibetan world unlike that of other Theravada and Mahayana Buddhist schools of thought.

Buddhism has evolved and changed depending on the circumstances and geographical separation. With changes in religion, come changes in practice. And when there are changes in practice, there are changes in the emphasis, use, and meaning of music – even between different sects of the same religion.

Buddhist Music History

Historically, Buddhist music has had many characteristics as it evolved into what we see today. As Yun stated, “…Buddhist music is based on a need to respond to changes in society in order to provide the most appropriate and suitable methods to help purify the hearts and minds of the public” (Yun 22). To help analyze the evolution, taking a close look at the historical context is paramount.

As far as Buddhism goes, we can see an origin story sprout in India during the Maurya Dynasty in 317 – 180 B.C.E. where King Asoka spread the teachings of Buddhism with great effort resulting in a time period of many developments in Buddhist music, according to Venerable Master Hsing Yun in his book Sounds of the Dharma: Buddhism and Music (4). Buddhist music during the Maurya Dynasty found an “inclusion of copper gongs, drums, flutes, conch horns, and harps in Buddhist ceremonial music” (4).

As Buddhism spread, Tibet began to be influenced by this new religion by about 641 C.E. (O’Brien 2013) where the Tibetan traditions of Buddhism “encouraged the use of song and dance in certain ceremonies” (Yun 4-5). Even Dalai Lamas were seen using instruments such as drums, windpipes, spiral conchs, and trumpets (Yun 5).

Buddhism in China

Apart from the variety of musical instruments of the Buddhist population, a unique look at a single country may be very helpful in analyzing the evolution of Buddhist music. Buddhist music in China plays a major role and even leads to new innovative musical notation.

When Buddhism was first introduced to China, the emphasis was generally on the translation of scriptures and the teaching of the Sanskrit Buddhist hymns (Yun 5). The absence of traditional hymns led monastics to recompose and adapt classical folk songs along with pieces commonly played for the royalty of Japan and the higher class of the Imperial Court, which led to the distinction of traditional Chinese Buddhist music dating back to the Wei Dynasty of 220 – 265 C.E. During this period, the son Cao Zhi was renowned for his singing and compositions and is credited to writing the first Buddhist hymn in a Chinese style which served as the foundation for Chinese Buddhist development (Yun 6-7).

In the Tang Dynasty, Buddhist music in China had become entirely Chinese and was actually very popular after the Chinese Buddhist style began to adopt more folk-like aspects and “flavor” (Yun 9). This Chinese music actually represents a reform in the style of singing and chants, and even makes use of a new system of musical notation (Yun 9). A very big step for China all thanks to Buddhist music.

Define Buddhist Music

Concerning ourselves with the types of Buddhist music can be as interesting as the history behind it. Buddhist music is described as “being strong, but not fierce; soft, but not weak; pure, but not dry; still, but not sluggish..” (Yun 22) all with the purpose of “purifying” one’s heart. To begin, Buddhist music can be separated into two kinds: chant, and instrumental.

Chants

The religious benefits of chant are not only personal but for a grand tradition. By practicing chants, we are preserving the words of Buddha since chants used today are said to be the same as the Buddha had used (AMTB) – directly credited toward spoken traditions handed down from generation to generation. Other benefits of chant are: it can help remind one of the Buddhist teachings, helps aid the memorization of the text, helps purify the karma of the body, speech and mind, can even be used as a preparation aid for meditation (Bhaskar 134). The text that is chanted is called the mantra (mantrə) which can be a sound, syllable, word, or group of words and is considered capable of “creating transformation.” Shomyo is the prominent style of Buddhist chant in Japan and can involve many people, even occasional drums.

As an example, “Aum” is a type of chant that represents the universe, the past, present, and future, all that was, all that is, all that will be. The three states of consciousness is represented by the letters themselves:

- A = alert

- U = dreaming

- M = asleep

(from AMTB.org)

Intonations or chants of sutras composed in China were also held as recitals, dating back to the origins of Buddha as traditional Buddhist music (Yun 7).

Instrumentals

The Tibetan Buddhist involve many varieties of music making, including chants and instruments. In fact, Tibetan Buddhism has the most widespread use of instruments for music and dance for certain ceremonies – even Lamas are seen using instruments (Yun 5).

The instruments would include the Dungchen or Rag-dung (prayer trumpet), Tibetan Ceremonial Drums, Tibetan horn, the damaru (drum), Tingsha (small symbols), Shaman’s bell, Meditation Bowl Gong (a.k.a. Singing Bowl). Outside of Tibet, the most widely used Buddhist musical instrument was the shakuhachi, a bamboo flute. Japanese monks called the Komuso began playing these flutes as early as the 13th century. Shakuhachi players would mostly play Honkyoku folk songs and traditional pieces for the instrument.

Modernizing Buddhist Music

The author of Sounds of the Dharma not only had research in mind. Yun’s goal involved finding out how best to go about modernizing Buddhist music. The most concerning observation he found was that the lifestyle common to most people today is very busy and quite stressful. Where is the time and place to take part in any kind of “spiritual refuge”? The daily of most people can result in the loss of one’s personal connection to the more spiritual aspects of life. Yun was convinced that “the pure and clear sounding melodies of Buddhist music provide a way to communicate the higher spiritual states of mind that are advocated by the Dharma and can serve to enrich and re-energize the hearts of the people” (Yun 22).

After his research, he found that Buddhist music has worked in the past to aid in drawing people into the Buddhist community, where a majority of them would be slowly transformed spiritually due to the constant contact with the teachings.

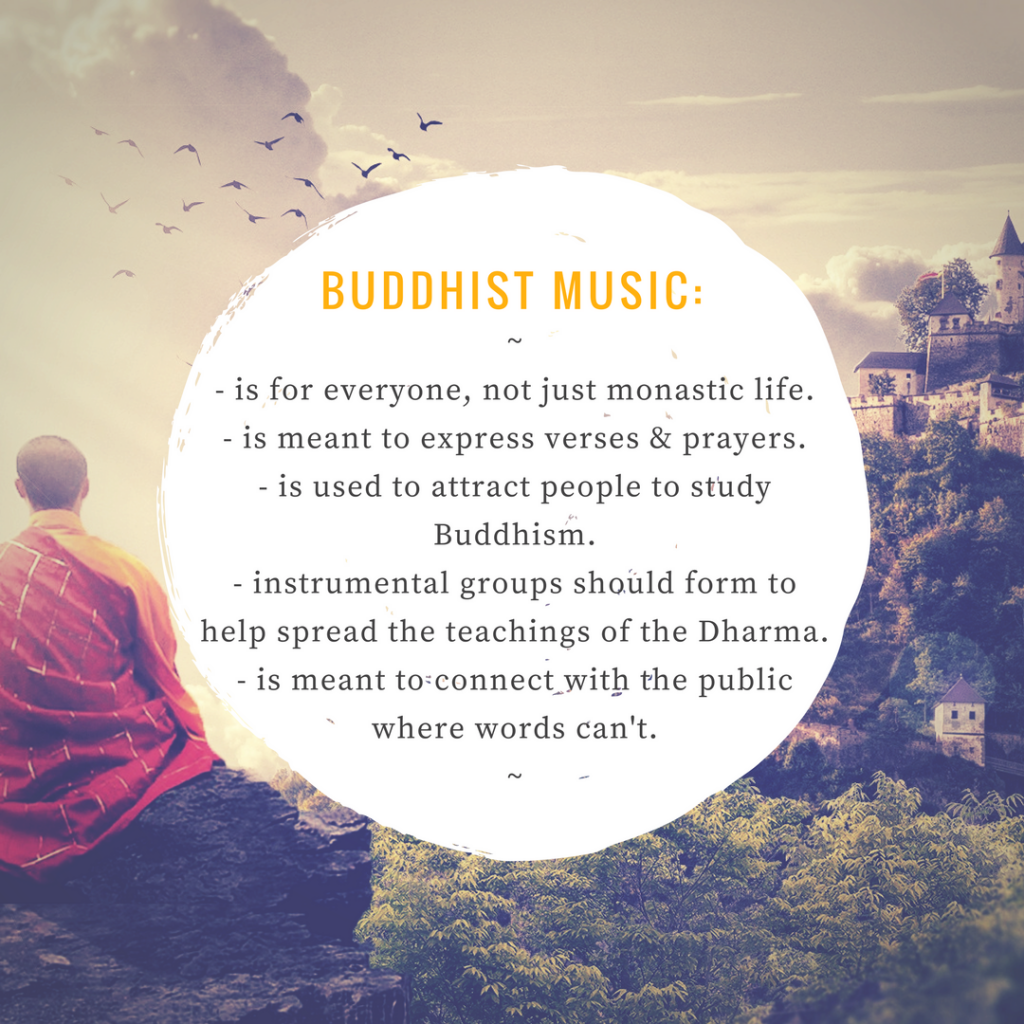

His findings left him to create five guiding principles:

1) Buddhist music should not be strictly for temples and monastic life but spread to the general public.

2) Need for creating new musical pieces in addition to Buddhist verses and chanted prayers.

3) Music should be used to attract the public to study Buddhism, which means more advocation in the use of music.

4) Buddhists should start to form bands, choirs, orchestras, classical music troupes, etc. to help spread the teachings of the Dharma.

5) New musical talent can help mark in Buddhist History.

As Yun outlined, Buddhist music is a tool to help reach out to the general public and express a relatable aspect – for everyone can connect to music in ways words can sometimes hinder the willingness to learn.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Conclusion

Buddhism, just as any religion, has its sects and differences between them so it is no surprise to find a wide variety in such a widespread religious practice. From instruments to chants, we find Buddhist sects have many similarities, the biggest being the use of instruments. Tibetan Buddhism is by far the sect of Buddhism that uses an extensive array of musical instruments not found in any other sect. Although music-making is different throughout the types of Buddhism, the use of music stays generally the same. In the Treatise of the Perfection of Great Wisdom, one of the Buddha’s teachings states:

To build a pure land, the bodhisattvas make use of beautiful music to soften people’s hearts. With their hearts softened, people’s minds are more receptive and thus easier to educate and transform through the teachings. For this reason, music has been established as one type of ceremonial offering to be made to the Buddha (Yun, 2).

What is your opinion? Leave a comment below!

________________________________________________________________

First draft written: November 6, 2013

Second draft written: January 25, 2018

Final draft written: March 26, 2024

Sources

- Bhaskar, V. S. Faith & Philosophy of Buddhism. Delhi, India: Kalpaz Publications, 2009. Print.

- “Buddhist Sects, Schools & Denominations.” Buddhist Sects and Schools. ReligionFacts, 5 July 2013. Web. 07 Nov. 2013.

- Chin Kung, Master. “The Four Kinds of Buddhism Today.” The Four Kinds of Buddhism Today. AMTB, 25 June 2003. Web. 07 Nov. 2013.

- “Mahayana Buddhism: Tibetan Buddhism, Dalai Lama.” Mahayana Buddhism: Tibetan Buddhism, Dalai Lama. BDEA Inc. & BuddhaNet, 2004. Web. 07 Nov. 2013.

- O’Brein, Barbara. “How Buddhism Came to Tibet.” About.com Buddhism. ABOUT.com, n.d. Web. 07 Nov. 2013.

- Shr Heng, Lyu. “Development And Mission Of Theravada And Mahayana Buddhism In An Era Of Globalization.” Religion East & West 11 (2012): 45-51. Academic Search Premier. Web. 7 Nov. 2013.

- Wong, Deborah. “Mon Music for Thai Deaths: Ethnicity and Status in Thai Urban Funerals.”Asian Folklore Studies 57 No. 1 (1998): 99-130. Print.

- Yun, Master Hsing. Sounds of the Dharma: Buddhism and Music. Taiwan: Buddha’s Light Publishing, January 2006. Print.

- Zhuang, Ge. “A Survey Of Modern Buddhist Culture In Shanghai.” Chinese Studies In History 46.3 (2013): 79-94. Academic Search Premier. Web. 7 Nov. 2013.

0 Comments