Written by Chase Chandler on May 17, 2016.

*Disclaimer: this article was written during my studies at Cal State University, Fullerton as a graduate student of music composition under Dr. Ken Walicki. My opinions have changed drastically since I wrote this article, but it serves a purpose. As controversial as this article can be, my greatest wish is to spark a conversation. If you agree or disagree, PLEASE start a conversation – with someone you know or with me personally by commenting below the article on this page. Happy reading!

Music and Image: Art is Undead

Musical trends have shifted many times throughout history and with the inventions of the information age, music has always been at the forefront of entertainment in each new media outlet. Once the radio and recorded music became widely available, the attitude toward music shifted greatly. Professional level music was no longer a travel destination, but part of the readily available home appliance called the radio (or radio set). With the introduction of the television, the audience’s attention was no longer caught by mere sound, but by image – moving images. With image being the new medium for captivating entertainment, music could no longer stay on the “cutting-edge” without image; therefore, television forced image onto music. With the almost sudden introduction of available information provided by the internet and home computers, music is still changing to suit the times and attention of consumers. Unfortunately, image remains the primary means for selling music.

Music and image have a complicated relationship that has recently blossomed in the last half a century with the invention of the television. For aid those interested in music theory and music philosophy, I will be analyzing this relationship and the American society to learn how advertisers manipulate society. Advertisements are constantly trying to attract consumers by exploiting societal interests, so an assumption will be made: advertising can offer an accurate representation of the American culture’s values and aesthetics. The use of music has changed drastically over the last thirty years based on the role music has played in advertisement. Music has shifted from the quality of the composition to the attraction factor of the artist, from the strategy shift from jingles to singles, from music involvement and forefront to music background behind image. The value of music is not realized by society, while the power of music is exploited by advertisers. Art is not only dead to the unknowing American public, it is undead because it is continually used as a mere manipulating tool to attract consumers in a capitalist society. Music is forced to breathe.

Image and Advertising

Advertising began as a simple means to spread the word about items for sale, but with the emergence of the industrial revolution and the ever-increasing amount of businesses, the heavy competition for consumer attraction has placed an equally heavy importance on advertisement. The first printed advertisement was for a simple prayer book for sale in 1477, by the Londoner William Caxton, seen in Figure 1.

Notice there is no addition of image associated with the item being sold (apart from the tradition text style from the time period). Around this same time, labels were being placed on medicinal remedies and “official announcements, programs, menus, and guides” were being printed as a means for communication. It wasn’t until 1625 that the first newspaper advertisement was published promoting a book and even then, the reader’s attention was caught by the title word advertisement, included in the paper. The first paid newspaper ads in America began in the 1704 publications of the Boston News-Letter. Benjamin Franklin was the first to create ad illustrations for an American newspaper, Pennsylvania Gazette in 1760 seen in Figure 2.

It’s important to notice that the typography leads the eye toward names and products. The image-oriented advertising grew to consume much of annually printed materials such as local newspapers. In this 1884 ad seen in Figure 3 (below), its entire allotted section is dominated by an image of the product.

In 1911, magazine ads began to use sex-sells slogans (such as “A Skin You Love to Touch”) alongside provocative images of nude women (an example seen in Figure 4 shown below). Corporations began to seek ad involvement in every printed public publication.

As the radio became more a part of the American life, advertising was quickly changing to suit the new medium of entertainment. The first music groups to be advertised on the radio during the early 20th-century were the Browning King Orchestra and the Kodak Chorus (“Kodak” being the product name). With the success of radio advertisement, commercial expenditure rose to $310 million by 1945 (eventually rising to $18 billion by 2000). But advertisement soon evolved to meet the new medium for entertainment, the television.

By the late 1940’s, the television began to find its way into the households of American families and around ten years later, major television programs begun to move away from radio style formats (audio and static image), such as The Tonight Show hosted by Steven Allen in 1953 and Peter Pan in 1955. Psychological studies and analytical research grew more popular as the demand for retentive advertisement increased among the corporate competition. The Public Opinion Quarterly published in 1950, had interesting “factual” observations from the article Some Psychological Factors in Pictorial Advertising, which stated: “One function of mass pictorial advertising… appears to be to force the audience to regress to an infantile mental level… the consumer is then more likely to take the action demanded of him.” In 1958, the Journal of Marketing was already publishing articles about how to increase advertising success rates. For example, the article Effects of Injecting “Local Color” into Advertisements from the July, 1958 issue of Journal Marketing reads: “…the geographic locale of the person or thing featured in an advertisement is of much less importance than the subject matter… it is the what, not the where which counts.” But the psychology behind image drastically changed as a new venture toward music and image came about in 1980.

MTV (or Music Television) launched on August 1st, 1981 and forever changed the face of music and television. No longer was music merely listened to, it was watched. The art of the music video begun to emerge as the popularity of MTV increased. Artists were now seen, not just heard – not only was their sound idolized, but their appearance as well. The American culture began to take shape around the music and the bands that played on MTV. Corporations desperately tried to associate their brand name with the popularity of MTV and the now commercialized, profitable music. The first rock tour sponsorship took place with the perfume company, Jovan, and the Rolling Stones during their 1981 tour (the same year MTV first aired). This sponsorship deal consummated “the marriage of rock and advertising,” after which major endorsement became the norm (an example poster can be seen in Figure 5 below).

Corporations began to make more effort in involving their brand in popular trends, in turn increasing more advertising. As an example, Apple set the new standard of advertising in 1984 by spending $900,000 on a Macintosh promotion during the aired Super Bowl. The early 1980’s was a new beginning for corporate involvement on television. Soon the home computer became the next popular means of entertainment, and as with any new shift in technological advancement, advertising strategies quickly shifted to fit the new form of entertainment.

The home computer was more easily accessible and affordable by the year 1995 when Windows ‘95 was released to the public. More homes had computers and online traffic increased. Advertising had already made it on the web, as more people were “surfing” the internet by 1995. On October 27, 1994, the first HTML banner advertisement was created for the site HotWired (see Figure 6 below).

Notice the colorful typography and the demand for action (to click “here”). This set off a chain reaction of new ads: the first keyword ad in 1995, the first mobile ad in 1997, Google Adwords in 2000, pop-up/pop-under ads in 2001, in-video/participatory/pre-roll ads for YouTube in 2006, behavior-based ads for Facebook in 2007, in-text ads in 2008, finally arriving at the most recent creation of advertisement, the viral ad in 2010 (such as the Old Spice commercials). Though ways to block ads were developed, new ad techniques always rose to the challenge. Each new way to shine a company brand or product quickly became the norm, such as in-video advertisement. Ever since ads for online, streamed videos was invented for YouTube in 2006, almost every website with video streaming begun to take advantage of this new tool. Nowadays, every TV channel associated website involves in-video advertisement that is almost impossible to block or prevent.

Throughout the evolution of advertising, there has been a great shift in the use of image. The first ads were merely text but soon begun to involve images, which started a chain reaction to where we are today, where ads rely heavily on image. If you look at the use of branding, there’s one logo that represents an entire company, but even today’s standard logo style has simplified. Take the company Instagram for example. Their old logo had a clean-cut camera with texture, lens, and parts in detail. Their new, recently released logo is very simplistic, only involving shapes and colors (seen in Figure 7 below).

No longer do we have intricate logos. The last is now gone. It seems after 60 years of advertising psychology and commercial research, the marketplace is now unified through one ideology: the best distraction is simplicity. Fewer words, more simple images. I believe music has felt a similar wave of corporate realization, where simplicity is always better. If image is meant to persuade readers into buying, then music is a similar tool in commercialism. Image is the art of static moments, but music is an art felt and experienced over time. With simple music, listeners have less to organize and comprehend, leaving them vulnerable to a commercial’s message. Looking into the depth of the relationship between music and image always reveals the rippling effects of television and the introduction of music videos. And nothing changed the face of music and image more than MTV.

MTV and Image

With MTV came the popularity of singles and the associated band or image. Similar to the way presidential elections started gearing toward who “looks better,” the television also begun to add a new dimension to the music. MTV, or Music Television, aired on August 1st, 1981 with the first broadcast stating that music and television will be forever changed. And it was a very accurate statement indeed.

Why did MTV and the introduction of music videos really change the face of music and image? Image had already begun to shift to simplicity and eye-popping colors, but music was it’s own industry set apart from image before MTV (or really before the television). In the American consumer society, the industry of music lends a personal touch to each consumer. For instance, music is listened to over time and must be experienced; therefore, the music industry sells personal experiences. With the combination of the product “music” and the almost debilitating effects of image (or video), MTV utilizes both personal experience and distraction. Through the experience of music videos, MTV is selling proposed “trends” of music and culture. “Music consumers can be aptly portrayed as ‘individual consumers who have strong faith in their own taste,’” giving music the power of mass customization. But when MTV defines consumer “taste” for the consumer audience, it directly changes the game for the music industry. Popularity is set by MTV, and shows positive results in album sales. Once a single was played on MTV, it became popular and sold albums, making MTV a powerful tool. The original purpose for MTV was to sell more music through television exposure, in hopes for more tapes, records, and video sales to combat the recession of the music industry in the early 1980’s. But soon after they first aired, MTV became an “authority” on musical trends, using music and image to influence their vast audience.

The advertising age grew with more psychological studies and as early as 1939, Theodor Adorno was hired by the Princeton Radio Research Project and was documented as saying, ad psychology is an investigation on an “administrative technique [for] skilled manipulation of masses.” It is not just the power of song that makes advertising successful, but the way in which they manipulate music by “studying, indexing and aggregating the effects.” Because of corporate involvement in MTV, revenue was always on the mind of TV channel producers. In 1983, David Geffen of Interscope Records and Dreamworks Studios (at the time) defines the advantage of this new medium for art:

MTV is a very effective tool in exposing and breaking new artists. In turn, it’s stimulating and encouraging recording artists to expand their creativity both visually and conceptually. Now the music industry can become the predominant art form through which the new generation seeks to express itself. We – music in video – can monopolize the imagination of a new generation.

It is wonderfully coincidental that musicians and videographers have a place to shine their new inter-collaborative works while at the same time Viacom Media Networks (who own MTV) make a profit. MTV carried out its original purpose and did it well because they were “monopolizing” this new-found art medium. A.C. Nielsen released a survey in 1982 involving 2,000 respondents who were MTV viewers from the intended demographic group. Out of this survey group, 85% watched MTV and on average viewed it 4.6 hours a week. And from this same group, 63% reported purchasing “an artist’s album after viewing a clip featuring the artist’s music.”

With the great success of MTV, corporations from the entertainment industry took the hint and began following in their footsteps. Paramount Pictures produced music videos in order to advertise their movies such as Flashdance (1983). Gordon Weaver from Paramount Pictures later explained that $3 million was spent promoting Flashdance, incorporating music into all radio and TV commercials after realizing the target audience for motion pictures was the same for MTV. “If you have a single… the spots [or commercials] are like cross-pollination.” MTV began a domino effect, encouraging most of the entertainment industry to involve more music and better yet, singles like MTV was doing. Once a single becomes popular and well-known, then every commercial’s brand or product will be instantly recognized solely based on the music. That is why Paramount Pictures involved music in every advertisement they could – to provide as many recognizable and memorable cues as possible.

MTV took the next step toward promoting music through video and successfully altered the way advertisers utilized music. Manipulation of the consumer audience through image and music became a powerful force of distraction. Advertisement has always and will always ride the tail of public interests and popular trends. As soon as MTV proved singles and artists were popular, advertisement never looked backed and completely fell head over heels.

Corporations are expected to pursue monetary gain and use many tactics (often involving manipulation), but what about the artists and musicians backing up the new-found musical image created by MTV? The shift from quality of music to quantity of music production was not necessarily the artists’ fault. The quality of art is not as important as its ability to manipulate in advertisement and when it comes to selling, whatever is deemed popular becomes the next best thing to involve in a commercial. But when music first began to help to advertise, the technique was to make the music as catchy as possible. Lyrical songs were written specifically for commercials, also known as jingles.

Before 1981: Jingles

When the marriage of audio and visual began with the first television broadcasts, most commercials began with static images and radio-style announcements. As competition for consumer popularity increased, so did advertising creativity and captivation techniques. After taking a survey of 38 prevalent commercials from 1948 to 2015, the trend for music singles and utilizing the “rock band” image began immediately right after the first broadcast of MTV.

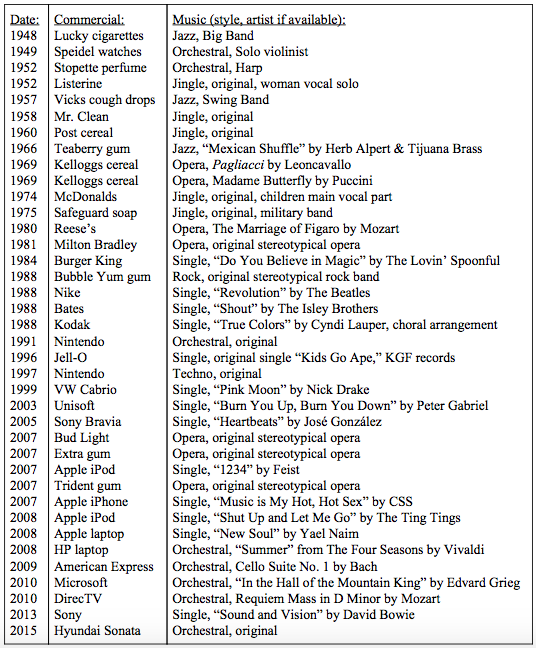

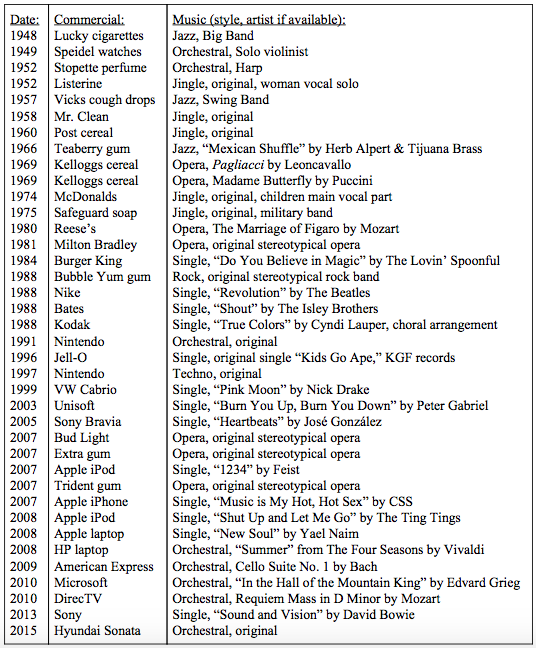

These 38 videos are listed in Figure 8 (see below). Out of these videos, there are three commercials that feature jazz music, five that feature an original jingle, seven with references to opera, eight with orchestral music, and thirteen with hit singles (all of which date after MTV). All commercials referenced in this paper are from this list of 38 commercials.

The television began to make its way into the American households by the late 1940’s and commercials evolved to fit the new medium. Because the transition originated from the audio-only radio programming, commercials only slightly took advantage of the moving image. One of the first commercials from 1948, portrays an image of the tobacco leaf with the Lucky brand of cigarettes. The only entertainment in this commercial is a jazz big band playing in the background. Apart from the added image, the simplicity of the audio sounds similar to a radio broadcast. In 1952, the company Listerine aired commercials for their mouthwash (or mouth antiseptic) and included research references and happy smiles. At the end of the 90-second commercial, there is a 30-second jingle of a woman singing about Listerine. Jingles were the new standard for commercials roughly four years after the television became widely popular. The longest standing jingle, which is still used today, is the original 1957 Mr. Clean jingle for their cleaning product. Apart from a quick ten-second break, the entire two-minute long 1958 Mr. Clean commercial is a strophic jingle explaining the uses of the product with demonstrations by the animated mascot (Mr. Clean) and a traditional American family (and even a wild squirrel that sings).

The Post cereal commercial of 1960, was very similar in that it also attracted to its audience by exploiting the image of the happy American family, only this time choosing the best and healthy (and “just a little better”) cereal. Though unlike most families, they were singing about their love for Post cereal. This twenty-second long vocalized theatre act is preceded by another scene of a fully costumed clown eating Post cereal with circus tents behind him (or it) and a male narrator describing how great the cereal is and how great the need is for the audience to buy some. These early commercials utilize music near the end of commercials so viewers are left with a catchy melody in their head. But what makes these jingles so catchy and were there certain techniques used? Three examples will be analyzed to further investigate the power of music in these early jingle commercials: Listerine (1952), Mr. Clean (1958), and McDonald’s (1974).

After transcribing a phrase of the music in the 1952 Listerine commercial seen in Figure 9 (see above), the first thing to notice is the chord progression of FMaj (I) to BbMaj (IV) to CMaj (V) to FMaj (I). This is only a snippet and the jingle does continue past what was transcribed, accounting for the unresolved melody ending on the 3rd of the I-chord. But the most interesting things to note is the use of rhythm on the word, “Listerine.” The company name received the most engaging rhythm: the dotted 8th-note, 16th-note, and half-note. This rhythm for “Listerine!” is the same for the first, second, and fourth measures – whenever the brand name is sung. The catchy jingle is constructed of similar rhythms and major chords. The repetition of the first and second measures set the motif, while the third measure (of all quarter notes) drives the listener to the downbeat of the fourth measure. This downbeat, unlike any other in this phrase, is not a quarter note, but the same dotted rhythm used for “Listerine!” The rhythmic gesture here points to the now recognizable motive of “Listerine!” This is advertising made “catchy.” The emphasized rhythm is on the brand name and as the last thing the listeners hear, there is a greater chance they will remember the brand name.

The longest standing jingle is from the 1957 Mr. Clean commercials with the original, nearly two-minute song. The transcription of the first four measures of the commercial reveals their strategy for a catchy melody (see Figure 10 above). Similar to the Listerine commercial, the product name (in this case “Mr. Clean”) receives the most memorable rhythmic motif. Each sentence is begun with “Mr. Clean,” with “clean” as the emphasis on the downbeat. In this example, the brand name is also used on a rhythmic gesture. The “catchy” jingle is built off the repetition of the 8th note and the pitches used. Because there’s a heavy emphasis on beats 1 and 3 (mostly due to the bass line), a similar strategy like the Listerine jingle can be found. The top note of the melody (Bb) is held while notes change in the accompaniment (much like the Listerine commercial’s high F, seen in Figure 9). The second measure hints toward the emphasized second chord of the chord progression: EbMaj (I) to Bb7 (V) to EbMaj (I). The chord structure is not only hinted at by the chromatic upward motion of the accompaniment, but also by melody going above Bb for the first time. This motion is counterbalanced by the downward arc toward the first Ab of the melody, which is the 7 of the dominant chord. The Ab, or the 7 of a dominant chord, has a natural pull downward (usually to the 3rd of the I-chord) that Mr. Clean exploits by leading the melody to the lower pitch of F. This pitch is then met with the same rhythmic gesture as the beginning on the text, “Mr. Clean,” which by repeating it solidifies the gesture’s strength. These manipulation tactics imposed on the melody help keep it memorable (and the text’s rhyming scheme is also of help). Another clever strategy is the range of the song, which only stays around Eb to C – an easy key for most all voice types and skill levels to be able to sing. This aids in the potential for singing along, which further lends itself to be remembered after the commercial ends.

The final example of jingle composition techniques will be nearly twenty years down the line: the McDonald’s Christmas commercial of 1974. It opens with the mascot, McDonald, singing an intro about giving presents while surrounded by a snowy, Christmas backdrop. A children’s chorus proceeds in yet another hoedown in a major key. Coincidentally, with each given example we’ve added two flats, now leaving us in the key of Db major seen in the transcription of this commercial jingle in Figure 11 (below).

A similar bass line to the Mr. Clean commercial is seen here as well, giving emphasis on beats 1 and 3. One of the interesting difference in this example is the difference in complexity – McDonald is now having children sing syncopations in a chord progression with more than three chords, including the first minor chord out of the three examples looked at thus far. The chord progression of this jingle is: DbMaj (I) to GbMaj (IV) to DbMaj (I) to AbMaj (V) to Bbmin7 (vi) to EbMaj (III). After this transcription, the EbMaj chord modulates back to the key of Db Major by progressing to the IV-chord and then the I-chord.. This chord progression is much more involved than the last two examples, and the melody is using different strategies for memorability. A similar rhythmic gesture to the downbeats is seen with “Give a hamburger” and “With some fries,” but the new rhythmic material is the syncopation of the eight note seen in measure one, two, and four. In the fourth measure, there are two eighth-notes emphasized on the offbeat (“happy”). The emphasized words of this phrase, with the syncopations included as well as the strong beats, are: “hamburger,” “someone,” “like,” “fries,” “shake,” “make,” and “happy.” The overall message is that McDonald’s food makes people happy (especially hamburgers, fries, and shakes). Notice as well, the borrowed chord Eb Major arrived on the word, “happy,” utilizing word painting as well as emphasizing euphoria in relation to McDonald’s fast food.

Out of the three examples transcribed, commonalities are found throughout each: the real message lies in the rhythmic gestures, exploitation of major chords, and simplistic bass lines of root and fifth derivation. The standard for commercial jingles was to be memorable and catchy, though the image of the commercial never necessarily matched the music (apart from dancing). The power of music and image wasn’t harnessed until the first broadcast of MTV, in which the relationship of commercialism and music brought about a major change in advertising.

After 1981: Singles

When MTV aired in 1981, image was immediately associated to the music. Commercialism, advertising, and corporate involvement soon grew to leech onto MTV’s success. Soon thereafter, jingles were quickly thrown out and TV ads latched onto singles, many involving the top-rated artists from the time period. Starting the same decade as MTV, commercials involved many hit singles, including songs from the Beatles, Cyndi Lauper, The Isley Brothers, and even more artists after the year 2000. Some artists even starting their career through commercialization.

The relationship between artist and corporation has always remained between the recording label and the musicians. But when image and video took the lead in entertainment, the corporate world began looking to capitalize on the success of MTV. Before music television, jingles were written for and only for their respective commercials, never as stand-alone music. So with the involvement of singles, comes the question of legitimacy. “What potential to empower can a song retain after an advertiser has used its power to promote a product or service?” But what if, though, the advertiser is the musicians themselves? The “music video is a hybrid of context and advertising, like a TV commercial for the album.” Commercials and advertising feed off the art expressed by music and in some situations, music videos can enhance the music. The entire history of opera involves image (characters and scene backdrops), without which would not have been the same experience. For commercials though, the problem is when the video and/or the product doesn’t match the music. When there is no effort to enhance the music, or vice versa.

Where is the line drawn between using music in ads and exploiting music in ads? Advertisements all use psychological strategies to draw attention, distract, and remain memorable, but with the emergence of the internet, the challenge changed. Consumers in America are now bombarded with ads every day. The market research firm, Yankelovich, surveyed over four-thousand average city dwellers and estimated that each person experienced 5,000 ad exposures per day. In order to stand out from the clutter, advertisement has begun to rely on artists to add a new dimension of organic realism to aid in consumer receptivity.

Dr. Jef I. Richards from Michigan State Advertising Association states: “Creative without strategy is called ‘art.’ Creative with strategy is called ‘advertising.’” We can assume this statement is in the context of the advertising world, but it still adds insight into the perspectives on art by advertisers. And although Dr. Richards did qualify his now popular statement by saying, “Art can have strategy, but it’s not a prerequisite, and the fact that some art does have strategy doesn’t automatically make it advertising,” his statement before still led to more questions. After contacting Dr. Richards about my questions, he replied,

Art is a powerful thing. And when you combine art with strategy, you channel that power in a particular direction. That’s what makes good advertising so effective. Yes, placing art in advertisement does make the audience receptive to the strategy.

The reception of the audience is the key emphasis in Dr. Richard’s follow up statement. Just like the psychological research in 1950 found that image reduces the cognitive activity of the audience, so then does art, but on a greater level. “One function of mass pictorial advertising… appears to be to force the audience to regress to an infantile mental level… the consumer is then more likely to take the action demanded of him.” If the use of pictorial advertising was to manipulate the audience, then where does that leave music? In commercials, images are used as a distraction for the eyes and music as a distraction for the ears. Art, both visual and audible, is used as psychological bait for the already bombarded consumer. If one commercial does not strike a consumer’s interest, then maybe another one with more colors and popular music will?

One example studied amongst advertising circles is the 1999 VW commercial featuring Nick Drake’s song, “Pink Moon,” directed by Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris. In this commercial, the only audio is Nick Drake singing with guitar (apart from brief background noise from a party). It begins with young teenagers driving to a party with “Pink Moon” playing in their VW Cabrio, but as they pull up to a rambunctious party, they decide to continue driving in the night. As they drive into the distance, the camera tilts up toward the moon to shine the VW logo. There is no dialogue in this commercial, only music. This approach was probably influenced by the fact Dayton and Faris were also music video directors. In this commercial, the use of music was to pull the listener into the simplicity of two audio layers: voice and guitar. The happy faces of the teenagers can then be correlated with the music as well as the VW car. The experience of the evening was sold as well as the experience of owning the VW Cabrio. This commercial has been hailed as a fine example of a well-balanced commercial of videography and music. Though not much about the car was involved in the “selling.” In this case, the experience was the main selling point. “For years ad agencies have realized that there’s nothing really to say about a car in a commercial, so they don’t sell the car, they sell an experience. Music evokes the experience.” Even though the artist has died before VW used the song, “Pink Moon,” album sales increased from “6,000 copies a year to 74,000.”

The technique of art in advertising has become mainstream after MTV first broadcast their music videos. Defining “art” within the context of commercialism can only be researched through art’s use in further pushing an advertisement’s strategy or message. Many music singles used in commercials were not originally written for that purpose; therefore, the music is true art for the sake of art. A corporation can choose to exploit the “artistic” value by employing it in commercials or advertisements, but generally, the art would still be considered art. A “good” use of a pre-written song, would be to involve it in a video that invites the listener to “hear the song in a fresh way.” But what if an artist knows of the commercial manipulation and yet allows for their art to be commercially used either for monetary gain or the potential for audience exposure? Because the intent is not for the sake of art, wouldn’t this be considered disingenuous to the world of art? No, as any struggling musicians or artist would answer because money is money. Igor Stravinsky took a commission in the late 1940’s for his Symphony in C and though written because of money, some argue that this commission “resulted in the composition of [Stravinsky’s] greatest symphonic work.” Artists need to make a living. Although not all commissioned works are as good a quality as Stravinsky’s Symphony in C, it’s proof enough that there is a possibility of good art for good profit.

“The Apple Effect” is a great example of artists becoming so popular from commercials, it jump-starts their music careers. “Apple has proven that every time an iPod is created, an indie band gets their wings.” Every single featured in Apple commercials quickly become top hits and sell millions of copies, at least in ads of the first ten years of the 21st-century. For instance, one of the first iconic iPod ads involves dancing silhouettes, bright colors, and the song, “Are You Gonna Be My Girl?” by Jet. After their commercial debut in 2003, album sales increased to over 3 million copies. Jet’s hit single wasn’t originally written for the commercial, very much like Feist in the 2007 iPod Nano commercial. After “1234” by Feist aired in the 2007 Apple commercial for the latest iPod, digital sales of the song almost doubled after being placed on the American Billboard Hot 100 singles chart in the same year. Apple’s commercial spiked their popularity as well. Yael Naim was awarded the Victoires de la Musique award for album of the year in 2008, the same year her song “New Soul” was aired in Apple’s iMac commercial. These Apple commercial examples all feature advertisements featuring music written before the ad release date. But can quality music be written specifically for advertisement, even though the intent is monetarily influenced? Most commercials involve singles from bands with some popularity, at least in a localized area, but one commercial with original music was picked out amongst the chaos of the advertising world.

Hyundai aired their 2015 “Camera Commercial” for the Sonata car model with custom composed music. Multiple Sonata drives down a swerving desert road with cameras following their every turn. The music first features a repeated piano motif with orchestral string accompaniment (the main solo instruments being piano and cello). One of the few breaks in the music is to allow for the revving car engine to be heard, but the intensity is made and kept by the music. The main chord progression defined by the cellist (the only acting bass voice) is a simply repeated Amin (I) to FMaj (VI) to Dmin (iv) to EMaj (V) with the piano receiving the main melody line. Stereotypical runs by a virtual violin section fill the gaps between the piano phrases and tubular bells emphasizing heavy downbeats. The video is only of the Hyundai Sonata driving on a swerving stretch of road in a barren desert. The music is the only interest provoking element in this commercial, aside from the quick video transitions between many shots of the same scene (a great way to maintain image-oriented distraction). Is this commercial utilizing the music correctly? Or is it primarily just using it as a manipulation tactic, because without the music it would be a rather uninteresting commercial.

Conclusion: Art is Undead

The aesthetic of art is arguable. The intent for art is interchangeable. The message of art and use of art is undoubtedly manipulable. As artists, we are far too concerned with the possibility of art dying rather than how it will be carried on. Our question should not be, will art die. Our question should be, will art continue to breathe? As Jacques Attali had emphasized in his book, Noise, after the industrial age came the repetition and mass production of music. Collective communication on a global scale has begun to blur the once distinctive lines between cultures and societies.

With MTV, popular media begun to define trends and standards of artistic practice. Desperation for popularity has been organically grown from corporate competition and because of this, our modern media-controlled society has spawned the culture of celebrity. The “idealization of the solitary artist” and “the reverence for autonomous authorship probably has roots in the Romantic Age and its mythology of the Promethean spirit.” The American capitalist society has generated a new strain for fame amongst the middle-class and corresponding advertising that prompts that desire. MTV and the image-oriented media have found so much success that a downward spiral has begun with no hope of an end.

The “art” involved in the image-laden globalization carried out by massive communication hubs such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr has destroyed privacy and devalued individual taste. Opinion is seemingly inorganic due to the heavy influence of social media and commercialism. Art is no longer grown, it is manufactured – always alongside the inescapable image of the media. Therefore, the media will always have influence over society due to looming standards set by the profit-driven image of popularity, manufactured by industry-led capitalism. Unless completely unplugged, an artist cannot escape media influences and with this happening on a global scale, we can expect to see more blurred lines between cultures and schools of thought (including philosophy, religion, art, and societies). The postmodern age of music will continue to develop. As lines between cultures blur and the world grow smaller due to mass communication, musical genres will also blur (fusions being an already existing example).

With each invention of entertainment, whether it be Monteverdi’s opera in the 17th century or the ability for mass communication through the radio in the late 19th century, music has always irreversibly evolved. Unlike technology (which always eventually becomes old, outdated, and in turn replaced by new technology), music continues to draw from its long tradition dating back well beyond the Medieval period (at least for non-Western music). Historically, instruments of a given musical tradition often became the associated image. In the Baroque period, with the creation of opera, the vocal lead would be associated with an opera. But it wasn’t until the Classical era that the image of the instrumental soloist was truly emphasized, especially with the invention of the concerto style. When recorded music became easily distributed with mass production, the attitude toward music begun to change. Its use-value was displaced: an “experience” of listening to live music was now an obtainable material via record album. Mass distribution also began to adjust to fit technological advances, because not only is there a desire to stockpile albums, there’s also streamable online music libraries with almost every album available at one’s fingertips. This globally available information will continue to change music (like it has already). The amount of time between the musical periods between minimalism and postmodernism is much less than the hundreds of years between the Medieval and the Renaissance. Creation of new musical styles is no longer special but lost amongst the vast genres already in existence. But our concern shouldn’t be aimed toward the need for musical innovation, because there is a larger issue at hand.

What is the next style of music, when there is no knowledge or aesthetic sense between good and bad music? The media and music industry is now so gnarled by monetary intention, that the quality of music is the least of their concern. If it sells, then it’s good for the industry. If quality is no longer of the greatest concern, yet it remains most popular and supported, then art for the sake of art is dead and art for the sake of money is very much alive. But music has been dying ever since MTV and image has taken its place in importance. Music has merely become a means to an end. The music industry is so profitable at this point that it will never die, but continue to lure the consumer society into purchasing more albums and related merchandise of the famous “artists” seen on TV. Music will just continue to be dragged by the industry through the oceans of the uneducated and the elitist will continue to alienate themselves from the horror they witness.

Music isn’t dead, it is undead – unable to organically live under the pressure of the media’s trend-setting ignorance, but forced to breathe for the sake of profit. The masses are well-equipped to study the intricacies of music, yet the ease of research (provided by the internet) has devalued investigation and a society with no zeal for further comprehension of the world around them (apart from what the media portrays) turns the population careless, in turn creating knowledgeable consumers. These consumers will continue to follow the trends set by the media like sheep led to the slaughterhouse by a hungry shepherd.

The only hope for the elitist community is to welcome the non-educated with open arms, teach music appreciation, expose them to more music, and point out the flaws of the music industry. Or fight fire with fire and attempt to make Schoenberg as cool as Captain America.

Appendix

Figure 1: 1477 London prayer books printed advertisement

Figure 2: 1760 Pennsylvania Gazette

Figure 3: 1884 Dr. Scott’s Electric Hair Brush advertisement

Figure 4: 1917 Woodbury soap advertisement

Figure 5: Jovan’s sponsorship of The Rolling Stones’ 1981 rock tour

Figure 6: first banner ad on HotWired website (now known as Wired)

Figure 7: Instagram’s new logo on the right

Figure 8: Table of 41 commercials from 1948 to 2015

Figure 9: Listerine Transcription

Figure 10: Mr. Clean Transcription

Figure 11: McDonald’s Christmas Transcription

Bibliography

I. Printed Sources

Breen, Marcus. “The Music Industry, Technology and Utopia: An Exchange between Marcus Breen and Eamonn Forde.” Popular Music 23, no. 1 (Jan., 2004): 79-82.

______. “Popular Music Policy and the Instrumental Policy Behaviour Process.” Popular Music 27, no. 2 (May, 2008): 193-208.

Bockstedt, Jesse C., Robert J. Kauffman, and Frederick J. Riggins. “The Move to Artist-Led On-Line Music Distribution: A Theory-Based Assessment and Prospects for Structural Changes in the Digital Music Market.” International Journal of Electronic Commerce 10, no. 3 (Spring 2006): 7-38.

Cohan, John Alan. “Towards a New Paradigm in the Ethics of Women’s Advertising.” Journal of Business Ethics 33, no. 4 (Oct., 2001): 323-37.

Denisoff, R. S. Inside MTV. NJ: New Brunswick, Transaction Publishers, 2000.

Evans, David S. “The Online Advertising Industry: Economics, Evolution, and Privacy.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 23, no. 3 (Summer, 2009): 37-60.

Frith, Simon. “Music Industry Research: Where Now? Where Next?” Popular Music 19, no. 3 (Oct., 2000): 387-93.

______. “Look! Hear! The Uneasy Relationship of Music and Television.” Popular Music 21, no. 3 (Oct., 2002): 277-90.

Hoffman, Miles. “Music’s Missing Magic.” The Wilson Quarterly 29, no. 2 (Spring, 2005): 28-38.

Kay, Herbert, and Dan E. Clark Ii. “Effects of Injecting ‘Local Color’ into Advertisements.” Journal of Marketing 23, no. 1 (Jul., 1958): 56-8.

Klein, Bethany. “As Heard on TV: A Critical Cultural Analysis of Popular Music.” PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2006.

McDonough, John. The Advertising Age Encyclopedia of Advertising. IL: Chicago, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2002.

Moore, Catherine. “A Picture is Worth 1000 CDs: Can the Music Industry Survive as a Stand-Alone Business?” American Music 22, no. 1 (Spring, 2004): 176-86.

Pope, Daniel. Making Sense of Advertisement. VA: Fairfax, George Mason University, 2003.

Rosati, Clayton. “MTV: 360 Degrees of the Industrial Production of Culture.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 32, no. 4 (Oct., 2007): 556-75.

Sivulka, Juliann. Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes: A Cultural History of American Advertising. CA: Belmont, Wadsworth Publishing, 2011.

Stephens, Mitchell. “The History of Television.” Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. NY: Grolier Interactive, 2000.

Sterba, Richard F. “Some Psychological Factors in Pictorial Advertising.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 14, no. 3 (Autumn, 1950): 475-83.

White, Eric Walter. Stravinsky: The Composer and His Works. CA: Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1984.

II. Online Sources

Elliot, Amy-Mae. “The Apple Effect: Ads That Have Launched Music Careers.” Mashable. Published on July 5, 2010. Accessed on April 20, 2016,,. http://mashable.com/2010/07/05/apple-commercial-songs/#yY7jcG6Rp5qm.

Graham, Mark. The First 30 Videos That Played on MTV. http://www.vh1.com/news/51387/…

Infolinks, “The History of Advertising,” Mashable, published on December 27, 2011, accessed on May 10, 2016,,, http://www.infolinks.com/blog/good-news/infolinks-in-mashable-com/.

Singel, Ryan. Web Gives Birth to Banner Ads. Wired. Published on October 27, 2010. Accessed on May 10, 2016,,. http://www.wired.com/2010/10/1027hotwired-banner-ads/.

Story, Louise. “Anywhere the Eye Can See, It’s Likely to See an Ad.” NYTimes. Published January 15, 2007. Accessed on May 10, 2016,,. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/15/business/media/15everywhere.html?_r=0.

III. Other Sources

Richards, Jef I. Email interview by Chase Chandler. Michigan State University, April 20, 2016.

Leave a Reply